After the SNB’s shock decision to remove the three-year-old cap on the CHF on January 15, economic indicators coming out of the Alpine country have been universally negative.

The KOF economic barometer, which gives an indication of the likely performance of the economy in six months’ time, posted its biggest fall since 2011 in February. Retail sales dropped 2.1 per cent on the month in January, even though shops slashed prices after the controversial ceiling removal.

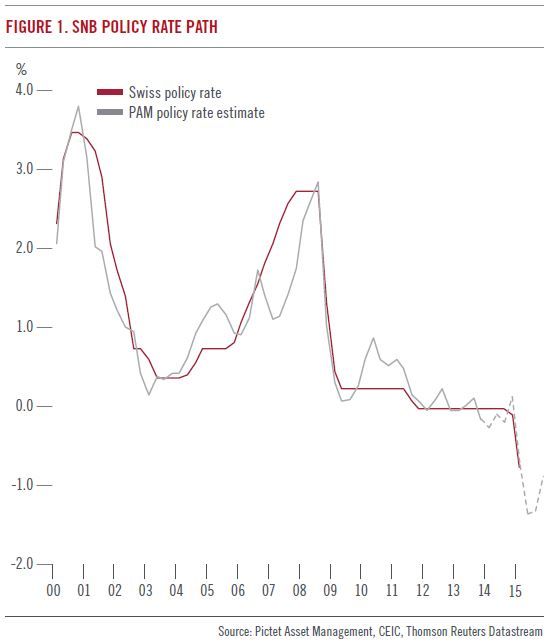

The central bank’s move to cut the benchmark Libor policy rate to -0.75 per cent – among the lowest in the world – is unlikely to shield the export-oriented economy. According to our estimate, monetary conditions have tightened by the equivalent of an interest rate hike of about 250 basis points, even taking into the account the SNB’s latest policy easing.

Swiss exports, which have remained resilient so far thanks to their high value-added nature, are about to deteriorate as manufacturers pass on the effect of currency appreciation. Our calculations show that the cap removal will have a net negative impact on GDP growth of about 2 percentage points this year, while it should increase the unemployment rate by 1 to 2 percentage points and lower inflation by 1.5 percentage points. We expect the economy to shrink by 0.4 per cent this year, after expanding 1.9 per cent last year. Consumer prices are likely to fall by 1.5 per cent, in our view, before rising again by 0.8 per cent in 2016.

We estimate that the CHF is currently overvalued against the EUR by a significant 15 per cent and 11 per cent on trade-weighted terms.

SNB and cantons

However, the economic situation is unlikely to deteriorate much further beyond 2015. Having come under fire for abandoning the cap so unexpectedly – a decision which we understand was taken under some political pressure – we think the SNB is keen to support the economy by easing monetary policy further, and to regain its credibility.

We feel the central bank prefers to use the benchmark Libor rate extensively as the key instrument of monetary policy than to intervene in currency markets, in order to avoid a further increase in foreign exchange reserves – which already stand at a record high level of CHF509 billion, or 78 per cent of GDP.

This is a politically sensitive issue – especially ahead of an October election -- and partly explains why the SNB had to abandon the cap in the first place, in our view.

Continued currency interventions to keep the CHF below the cap would have hurt profits on foreign holdings, which are the key source of funding for the country’s 26 cantons – the SNB’s biggest shareholders that traditionally receive transfers from the central bank.

In 2010, when the SNB ran up a CHF21 billion loss due to the franc’s appreciation, critics called on then-President Philipp Hildebrand to resign. In 2013, the SNB received a wave of complaints from municipal budget chiefs after scrapping its dividend. From its 2014 profits, the central bank granted CHF2 billion to the cantons and the government.

The SNB has already said the risk of losses on the bank’s foreign currency holdings was one of the reasons for abandoning the cap. SNB officials have also pointed out that the ceiling was supposed to be a temporary measure implemented during a period of high market volatility, which eventually lasted too long.

No policy U-turn

Whatever was behind the removal, we don’t think the SNB can afford a policy U-turn now, given the damage to its credibility. This is in spite of some political pressure – the Social Democratic Party, which holds two seats on the seven-member council that governs Switzerland, is pushing for the reintroduction of a cap (as well as a close scrutiny of the bank’s three-member governing board which it says leads to opaque decision making).

Instead, we think the SNB now has an implicit exchange rate target to prevent further CHF appreciation against major Swiss trading partners in addition to its interest rate instrument.

According to our equilibrium estimate for the policy rate in the second quarter of 2015 (see Fig. 1), we expect the SNB would take the Libor rate as low as -2 per cent in the event of strong upward pressure on the CHF or further deterioration in the domestic economy. This would be historically the most negative level for a central bank policy rate in the post-Bretton Woods period.

While interest rates are the SNB’s sole policy making tool at the moment, negative rates have had a limited pass-through effect to the real economy so far.

This is because the SNB treats bank differently depending on the level of excess reserves held at the bank -- negative rates only apply to those holding more than 20 times the minimal reserves, such as foreign and private banks and asset managers. Indeed, big Swiss banks and cantonal fand Raiffeisen banks – those specialised in retail and mortgage lending -- are broadly unaffected.

Therefore, we believe the SNB can improve the effectiveness of monetary policy by substantially lowering the minimum threshold level and broadening the scope of negative rates.

Lift from euro zone

The Swiss economy can also get a lift from its largest trading partner. The euro zone accounts for 45 per cent of total Swiss exports, about a third of GDP.

In the medium to long term, the euro zone’s economic recovery and the decline in geopolitical tensions in Eastern Europe should drive the euro higher against the CHF, improving Switzerland’s external competitiveness.

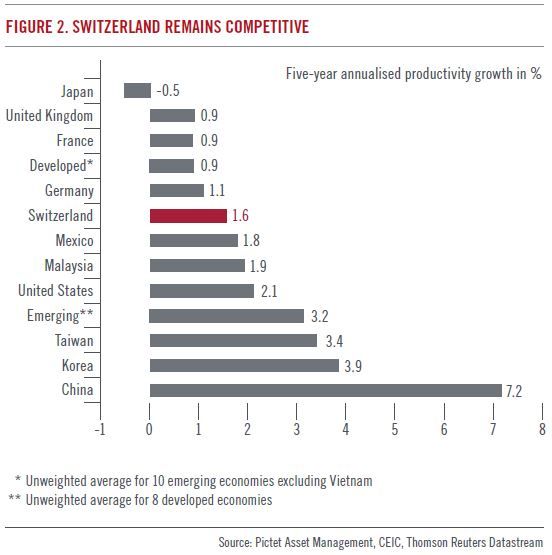

Structurally, Switzerland remains highly competitive. According to our estimate, productivity growth in the manufacturing sector stands at an annualised 1.6 per cent over the past 5 years, well above the average of advanced economies, thanks to low unit labour cost growth and high spending on research and development which allows strong innovation.

What is more, consumers are likely to start shopping again, lured by declining import prices and additional discounts from retailers, driving a recovery in economic growth next year, which we expect to come in at 0.2 per cent.

Nikolay Markov, Economist, Pictet Asset Management