If the currency markets were a stage, then the US dollar would be the star performer. Over the past four years, the US unit has gained some 25 per cent on a trade-weighted basis. Most remarkable has been its 14 per cent appreciation since the summer of 2014 – one of the strongest nine-month rallies on record. Investors in emergingmarket (EM) debt won’t be standing to applaud, however. For them, the US unit’s performance has been something to jeer.

That’s because the appreciation has exacted a particularly heavy toll on EM currencies over the past three years. In that time, the Russian ruble, the Brazilian real, the Turkish lira and the Indonesian rupiah have each lost more than 30 per cent against the US dollar. Even the Polish zloty and the Mexican peso – among the more resilient currencies in the developing world – have fallen about 16 per cent. This has been accompanied by an increase in exchange rate volatility which, in turn, has increased the currency risk inherent in EM local currency bonds. Research from the Bank for International Settlements shows that yields on EM local currency bonds tend to rise when currency volatility increases.

However, the trends that have held in place over the past three years are beginning to fade. The first quarter of 2015 has seen EM currencies find a more stable footing, suggesting that this long period of wholesale depreciation could soon give way to a new phase - one in which countries’ idiosyncrasies have a bigger influence on valuations. Indeed, the conditions are in place for many EM currencies to begin appreciating once more.

Not only are many currencies trading below their fair value, but reforms underway in parts of Asia and Latin America should also give rise to a profound shift in currency markets. Some currencies will begin to put this period of depreciation behind them.

Back to the 1980s

The decline in EM currencies can be traced back to 2011. It was at this point that developing economies’ expansion first started to slow. So began a narrowing of the growth differential between the emerging and developed world that has persisted to this day. Currencies lost another support during the summer of 2013, when the US Federal Reserve laid the groundwork for an end to quantitative easing and interest rate hikes. Since then, the forces bearing down on EM currencies have multiplied to include a slowdown in China and a fall in commodity prices.

The fall now looks excessive.

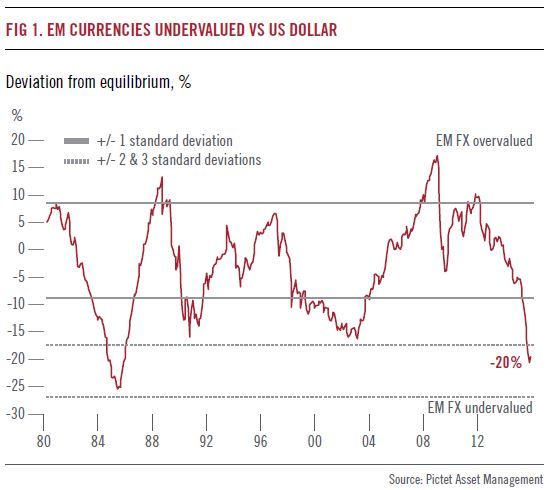

In the wake of their three-year descent, the 32 EM currencies we track are now trading at their cheapest levels against the US dollar since May 1985. This is the picture painted by our proprietary model, which uses a country’s consumer price inflation, productivity and net holdings of foreign assets to determine a currency’s fair value. In aggregate, we find that EM currencies are some 21 per cent undervalueda gainst the US dollar, or two standard deviations below their equilibrium rate (Fig 1).

So valuations clearly point to a rebound in most EM currencies. But what are the fundamental developments that currency markets have yet to reflect?

One is the prospect of an increase in EM exports. As economic momentum in the US, euro zone and Japan picks up, external demand for goods produced in emerging economies is also likely to rise, boosting output growth in the developed world. By our reckoning, the US, Japan and eurozone expanded at a yearly 1.8 per cent in second quarter, a rate that has historically coincided with EM export growth of 10 per cent annualised. True, the sensitivity of EM exports to world growth may have fallen slightly in the past few years because the benefits of past reforms are fading. Yet we believe the relationship remains sufficiently strong to lift EM exports by a considerable margin.

Higher exports would lead to healthier current account balances, which in turn would drive a recovery in emerging currencies.

Asia to lead the turnaround

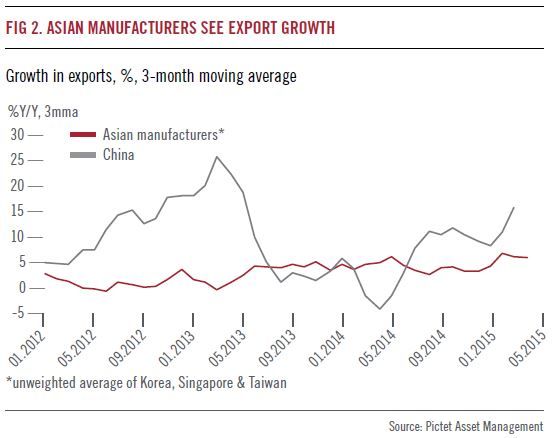

The manufacturing powerhouses of Asia – among them Korea and Taiwan – should be the first to benefit from advanced economies’ recovery (Fig 2).

There is already some evidence of this as Korea’s inflation-adjusted export growth rose an annualised 15.6 per cent in volume terms on a three-month basis in February. Low oilprices are also to provide a boost as they have improved Asian energy importers’ terms of trade – or the price of the regions’ exports relative to imports. A rising ratio is indicative of increased demand for a country’s exports and, by extension, its currency.

Historically, the rise in Korea’s terms of trade relative to the US has been a significant force in pushing the Korean won higher against the US dollar. Since 2013, the country’s terms of trade have increased by 12 per cent relative to the US. The Korean won has so far failed to respond to this shift, but we expect the currency to gain traction in the coming months.

But advanced economies’ growing appetite for EM exports is not the only reason why EM currencies might soon begin to change direction. Portfolio investment flows could also be a factor. With a growing proportion of developed market bonds trading at negative real or nominal yields, investors in need of income are short of investment options.

The yields offered by EM local currency debt securities could therefore prove too attractive to ignore. Not least because -at just over 5 percentage points above those of developed market bonds - they are two standard deviations higher than the long-term average.

Structural reform could offer an additional support. Reforms are gathering pace across parts of the emerging world –holding out the prospect of an improvement in productivity– a prerequisite for currency appreciation.

In Latin America, the beacon of reform is Mexico. Under President Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico has set in motion far-reaching structural reforms encompassing its energy, financial, labour, education and telecoms industries.

The country’s reform responsiveness rate, or the extent to which it acts on reforms recommended by the OECD, has reached 58 per cent in 2013-2014, above the EM average.

Encouragingly, the legislative phase of this reform processis already complete, and many policy changes are starting to make a difference. Official estimates show that labour market reforms – which involve modernising the outdated employment code, introducing hourly pay and reducing the scale of the black market economy – are expected to increase growth by 0.3 percentage points per year in the next five to six years. The government has said labour reforms would generate an additional 400,000 jobs a year on top of ones already being created.

Energy reforms – which include opening up the state-owned sector to foreign investment – could also boost the country’s growth potential. The IMF estimates reductions in electricity tariffs stemming from the energy reform could increase manufacturing output by up to 36 per cent.

China is another EM economy undergoing major reform that could result in a strong appreciation of its currency. A keypart of the planned overhaul involves China’s state-owned enterprises, where the government is looking to increase efficiency, attract private investment and improve levels of profitability and corporate governance.

Authorities are also working to phase out price controls in the water and energy industries – a measure that would remove the distortions that have led to wasteful investments in the country’s infrastructure and industrial capacity.

More recently, China has stepped up efforts to open up its capital markets to foreign institutions. So far, more than 30 foreign institutions have been given the green light to invest in the country’s RMB6 trillion bond market. This promises to be just the beginning of the process. Later this year, the renminbi may also become a constituent of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights basket, which would speed up the currency’s evolution into a reserve currency.

Taken together, these measures promise to draw investment into China and bring about a long-lasting appreciation of the renminbi.

All this is not to say the appreciation in EM currencies will unfold either quickly or in a linear fashion. Investors should expect to see a considerable divergence in the trajectory of individual EM currencies over the next several years. Even so, we foresee EM currencies gaining some 4 per cent per year against the US dollar over the next five years, led by Asia. The underlying, long-term trend is one of currency strength not weakness.

Patrick Zweifel, Chief Economist, Pictet Asset Management

Weitere beliebte Meldungen: