When a Nobel economics Laureate, a Harvard finance professor and an emerging market guru take the same dim view of developing economies, you’d expect the investment community to sit up and take notice. The combined intellect of Paul Krugman, Carmen Reinhart and Mark Mobius is pretty formidable after all.

But investors have done much more than prick up their ears. They have also voted with their feet. As the chorus of voices predicting an emerging market crisis has grown louder, bonds issued by governments and companies based in developing economies have spiralled lower. Year-to-date, the JPMorgan GBI-EM Index of local currency emerging bonds is down some 5 per cent. (Data covering period 31.12.2017-27.07.2018)

Still, it’s not the first time investors have been confronted with dire warnings about a credit and currency crunch in emerging markets. The same occurred during the "taper tantrum" of 2013, when the US Federal Reserve first signalled its intent to rein back quantitative easing.

The bears turned out to be wrong then. They are also mistaken now. And on several counts.

The sceptics' chief concern is the damage higher US interest rates and a strong dollar – the consequences of the Fed’s monetary tightening – could do to the finances of emerging nations.

Many developing countries are reliant on foreign investment to fund persistently high current account deficits. When US rates and the dollar head north, these economies find it harder to service their debts; they also struggle to prevent international investors from shifting capital elsewhere.

Inflation can be a headache, too. By increasing the cost of imports, a stronger dollar usually gives rise to inflationary pressures, making life uncomfortable for central banks.

This year’s sell-offs in Argentina’s peso and Turkey’s lira – countries with some of the largest current account deficits in emerging markets – speak to the naysayers’ fears. The peso and lira are down 32 per cent and 21 per cent respectively since the start of 2018. (Data covering period 31.12.2017-27.07.2018)

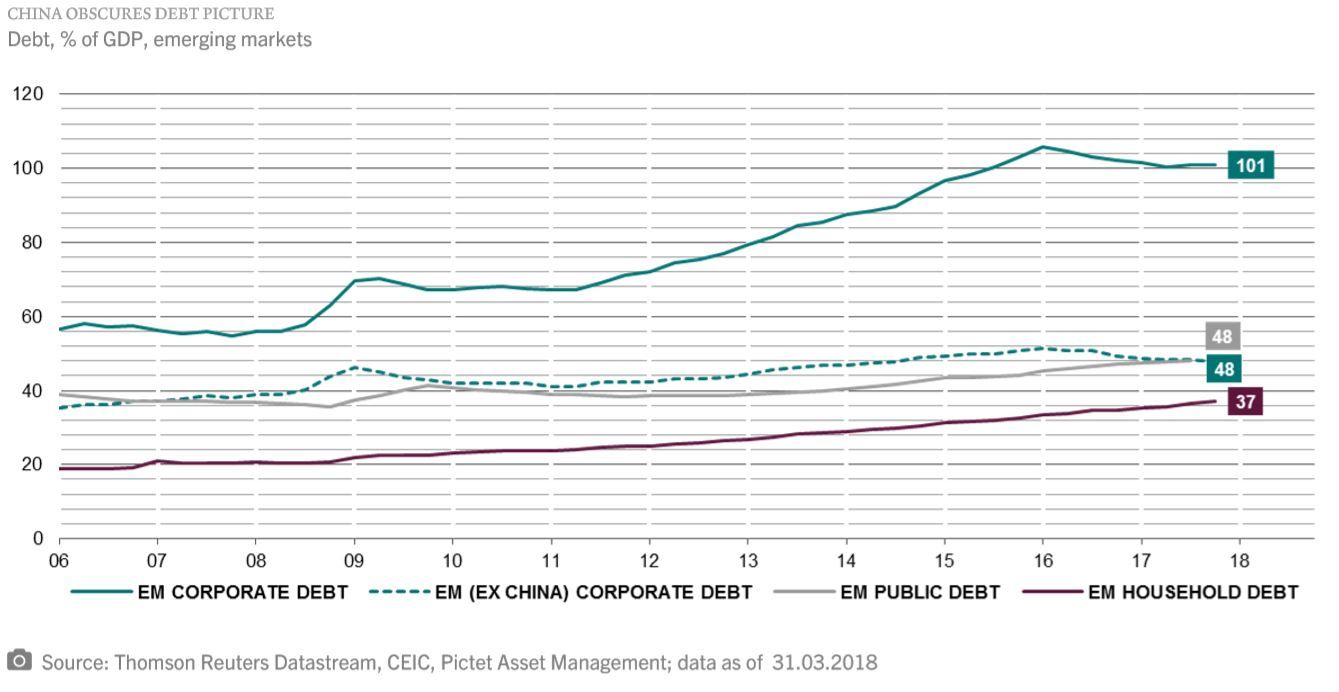

Making a bad situation worse, the pessimists say, is that corporate finances are barely any healthier. Since the US turned on the monetary taps in 2009, companies in the emerging world have taken full advantage of low interest rates, increasing their borrowing as percentage of GDP from about 80 per cent in 2013 to 101 per cent at the start of 2018.

With the bulk of those loans and bonds denominated in US dollars, the Fed’s tightening of the monetary reins threatens to make it harder for the private sector to pay back its debts, too.

Systemic risks contained

But it’s important not to overstate these risks.

To begin with, Argentina and Turkey aren’t representative; they’re emerging market outliers that have been punished for several mis-steps, not least the undermining of central bank independence.

The current account positions of developing economies more generally have in fact improved considerably since 2013. In aggregate, emerging markets’ current account surplus has grown from 0.1 per cent to 0.8 per cent of GDP over that time. Even among emerging countries with deficits, the gap has narrowed to 1.7 per cent of GDP compared to almost 4 per cent during the taper tantrum.

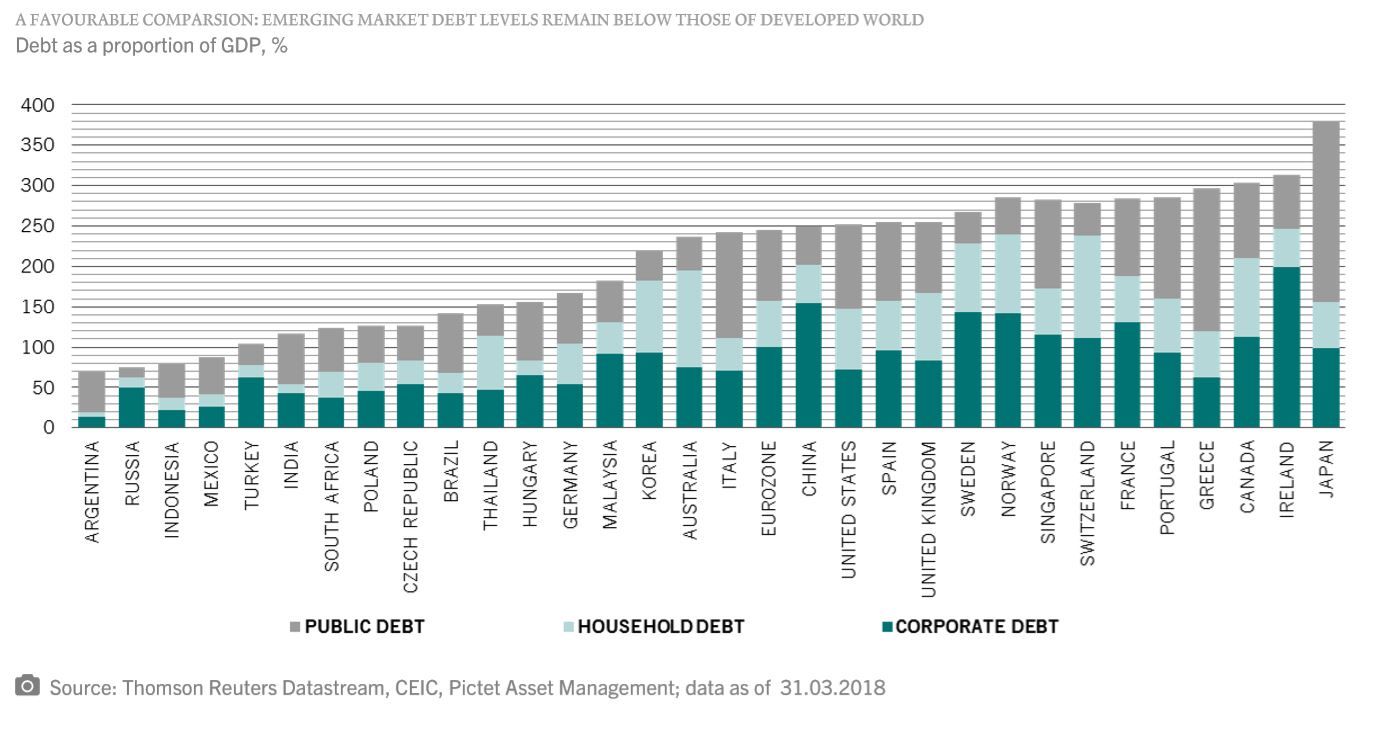

The notion that emerging market companies are awash with debt doesn’t hold up to scrutiny, either. True, Chinese firms have been big borrowers, but strip them out of the analysis, and the picture isn’t quite so unsettling: company debt as a proportion of GDP in emerging markets drops from over 100 per cent to just 48 per cent, a mere 3 percentage points above where it was five years ago. That compares to 72 per cent for the US, 100 per cent for the euro zone and 103 per cent for Japan.

Corporate borrowing up but rising at slower pace

Also encouraging is that borrowing is moderating across the developing world, China included. The credit gap – or the difference between the current and trend rate of private debt growth measured as a proportion of GDP – has been falling across all major economies. In China, the differential has dropped from a peak of 27 per cent of GDP to 17 per cent. In Brazil, India, Russia and India, the gap has actually turned negative.

What’s more, the proportion of “risky” corporate loans and bonds in the developing world (ex-China) is lower than it was during the 2008 financial crisis, according to a study by the Fed. (See Beltran, D., Garud, K. and Rosenblum. A. 'Emerging market non-financial corporate debt: how concerned should we be?' Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 2017)

In part, that’s because many of the firms issuing dollar-denominated bonds are exporters whose revenue is predominantly denominated in foreign currency. For these companies, when the greenback rises, the resulting increase in debt costs is offset by the extra revenue earned overseas.

What’s also been overlooked during this recent bout of turbulence is that increases in US interest rates aren’t necessarily bad news for emerging market assets or currencies.

As long as the Fed is tightening monetary policy in response to faster growth, the economic spill-over to the developing world should be positive. An analysis undertaken by Barclays bears this out. The bank found that in every US hiking cycle since the mid-1990s, emerging market currencies and bonds have tended to outperform developed world counterparts. (See ‘How I learned to stop worrying and love higher rates', Barclays, June 2018) The same picture emerges in our own study.

Of course, should the world descend into an all-out trade war, then all economies – developed and emerging – could suffer. But if, as we believe, the tariff disputes lead to improvements in how the world trading system functions, as the outcome to recent talks between the US and EU suggests, then the strong fundamentals of emerging markets should come to the fore.

Alain-Nsiona Defise, Head of Emerging Corporates

Mary-Therese Barton, Head of Emerging Market Debt