There has been significant demand for loans, both in the US and Europe, in response to ultra loose monetary policy and the global reach for yield. This has increased the volume of capital directed towards the asset class and has seen the total market size grow (a healthy development), while lender protections and prospective returns have declined somewhat (an unhealthy development).

For market practitioners the IMF does not raise anything particularly new but for the casual observer some of the points highlighted may be cause for concern. We believe that these issues have typically been well highlighted in the market and are certainly areas that we have discussed with clients in our secured loans and multi asset credit strategies.

Some of the highlights of the report are addressed below.

Burgeoning loan markets?

Since 2007, the outstanding volume of institutional leveraged loans in the US has almost doubled, now standing at over US$1 trillion, while by way of comparison, the European leveraged loan market is essentially the same size today as it was in 2007 (see chart 1).

The risk here is the nature of the end investor in each market and the length of their time horizons. Both markets have benefited from the growth of the collateralised loan obligation (CLO) market in recent years, as this has provided a near constant source of demand and represents longer-term locked-up capital. However, we believe there is risk associated with the shorter-term money in the US coming from retail investors, who are often more sensitive to price moves and market volatility, an investor base not present in Europe owing to the 'institutional only' nature of the market.

The reason behind the borrowing is significant

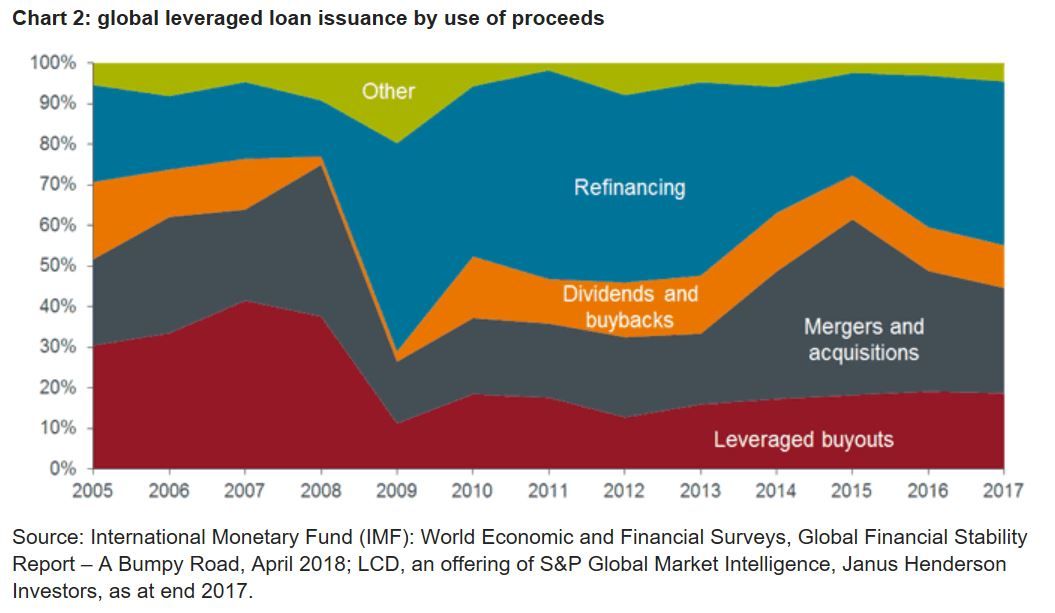

An important consideration for us is always the reason why a company is borrowing money to begin with. Typically, we view lending to businesses that are using the proceeds to fund leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as being inherently more risky than a refinancing or recapitalisation. LBO and M&A deals are typically new transactions, often carveouts from larger businesses and may come with new management with a strategy premised on achieving cost savings, which may entail significant execution risk.

In contrast, refinancings and recapitalisations typically involve companies that we often are already lending to, which means we know and understand how the business is managed. A chart in Chapter 1 of the IMF report (Figure 1.9) shows that while the portion of the market funding more speculative activity is increasing, it remains significantly below the levels seen before the financial crisis (see chart 2).

No escaping from the cov-lite craze

The criticism of the growth of ‘covenant light (cov-lite)’ transactions is fair and is a storyline that we cannot escape from as loan investors. The absence of covenants in the markets will potentially increase volatility in a downturn and may also reduce recovery levels upon default to below historical levels.

As investors, the ability to renegotiate higher coupons or equity injections to de-risk our loan investment as a result of companies breaching financial covenants is no longer available to us. As a result, investors in underperforming loans will need to sell their positions until a discounted price offers fair compensation for the increased risk of lending to companies that are underperforming. This is partly mitigated by the fact that the market is becoming more mature, with a less concentrated investor base, making it more liquid and easier to move underperforming companies out of the portfolio.

Outlook for defaults

We still think the near-term outlook for defaults is relatively benign. Given the strong market conditions, even companies with weaker balance sheets have been able to refinance, lowering debt service costs and extending maturities. Without near-term maturities and given low servicing costs, the probability of default decreases over the next year or so in a cov-lite dominated market.

The EBIDTA add back paradox

The IMF make a good point about the high level of EBITDA add-backs. This has been a negative feature of the market for some time now. As an example, these can include the forecast impact of cost saving initiatives that could take two years to realise. It is very optimistic to include these as part of the EBITDA when issuing a loan. This is why we construct our own models to ensure we are looking at the real leverage and true cash generation of the business, rather than using a heavily adjusted number or assessing a company on a ‘pro forma’ basis.

Summary thoughts…

The growth in institutional investor activity in the market is not an unintended consequence of the recent regulatory changes designed to ‘curb excesses’. CLO and institutional money has been involved in this market since the early 2000s, with our own dedicated loans fund launched in 2005.

As mentioned in the IMF report, there is less subordinated debt in capital structures today, which potentially means less of a cushion for senior lenders. We have previously highlighted that leverage levels (while higher) are not out of control and the equity contributions in deals continues to be high as a percentage of the total enterprise value of the business. This means that secured loans still have a very healthy cushion for absorbing losses in underperforming companies.

It is generally acknowledged in financial markets that the current credit cycle is well advanced. Therefore, there are deals coming to the market now, which are likely to struggle at some point in the future in our view. Thus, a cautious approach to investment in the loan market would seem to be sensible and our strategy is deliberately conservative — while we have historically underperformed in strong markets, we have proved more stable in tougher times.

The European loan market continues to look attractive, based on a healthy running yield, continuing strong demand and the low duration nature of the asset class.

However, we are not being complacent and continue to be highly selective regarding the loans going into our portfolios.

Weitere beliebte Meldungen: