On the Sidelines

"In Q1 I had the chance to travel and spend some time with our U.S. advisor and investor clients. While no two portfolios are identical, I was struck by one major commonality: the amount of cash and uninvested balances left in portfolios. On a recent trip to the West Coast, advisors frequently noted portfolios with 10%–40% (!) cash. These are probably outliers, given that the conversations occurred during the January/February correction and rally that seemed to paralyze investors. Moreover, allocation trends from our Portfolio Research and Consulting Group indicate that cash levels are running only slightly above their longer-term averages. However, it stands to reason that as the macro storm clouds have gathered, investors would become more hesitant to expose their portfolios to market risks.

How Did We Get Here?

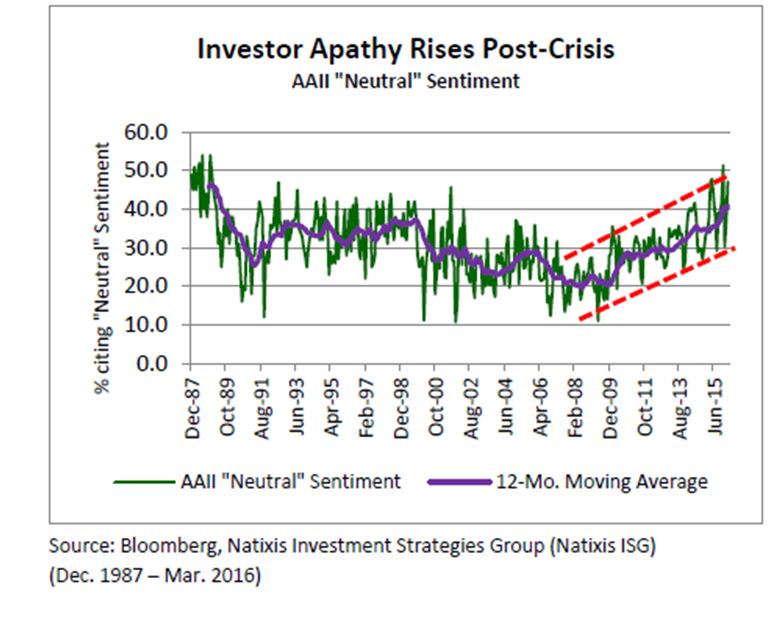

Investor apathy has been rising for some time. After two major bear markets since 2000, investors have become hyper-sensitive to volatility. This leaves them with a set of poor choices: Buy in mid-crisis hoping you’re at/near the bottom (“fear”) or jump in too late, after the market has already rallied significantly (“regret”).

While bullish and bearish sentiment can change quickly, data from the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) shows that the only constant since the 2008 crisis has been growing investor apathy as measured by investors who consider themselves “neutral” on stocks.

Adding to investors’ post-crisis confusion is a macroeconomic environment full of apparent risks. China either is or isn’t in the midst of a massive debt-fueled growth bubble. Greece, Brexit, and a refugee crisis are creating existential questions in the European Union. And collapsing commodity prices are pressuring emerging markets, impairing credit, and increasing geopolitical risks. No surprise that investors are perhaps feeling more skittish than ever.

Slow Death vs. Quick Death

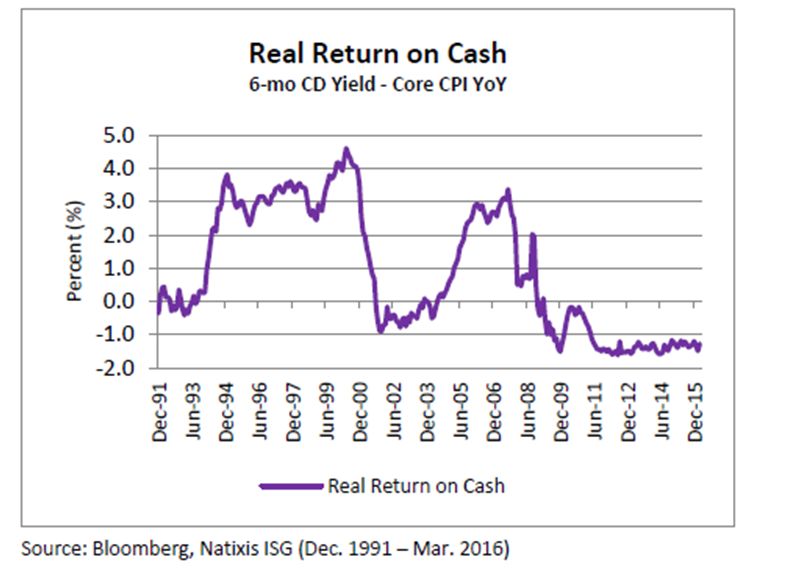

So if market outcomes are highly uncertain, shouldn’t investors be more cautious before committing capital? Yes, but cash is still an asset that is likely to have a negative real yield; that is, a return less than inflation. While inflation rates have fallen around the world, so have return expectations, so maintaining real purchasing power is still a challenge. Only in economies experiencing outright deflation would a near-0% return not be hazardous to real wealth.

The situation is no better for savers overseas. While inflation rates in Japan and across Europe are lower, cash rates are also lower and in some cases negative. Thus, for most global investors, moving to cash becomes a choice between an almost certain slow death in terms of losing purchasing power versus the possibility of quick death if potential risks morph into an actual sell-off.

Skeptical on Tactical

So if cash is likely to be a negative real return asset, are there any compelling reasons to stay on the sidelines? The most frequently cited argument is the “Dry Powder” strategy that goes something like this: The uninvested portion of the portfolio will be quickly redeployed in cheap assets once the sell-off or bear market occurs. Warren Buffett would be proud! However, Dry Powder sounds far better in theory than it works in practice. The strategy assumes investors will (1) recognize the value created by a sell-off and (2) buy the worst performing assets at the point of their highest perceived risk. Common sense and boatloads of academic research argue that this scenario is highly unlikely. Advisors with non-discretionary assets have much the same problem – convincing their clients to buy the stuff that’s getting killed. Advisors with discretion over client accounts are in a far better position, but they still have to overcome the downside inertia of the market and be willing to accept their clients’ second-guessing. While we applaud the purchase of assets that are temporarily “on sale”, we also have a healthy bit of skepticism about whether these tactical moves will actually be exercised. “Tactical” is fine, but be realistic about your ability to execute. (Automatic portfolio rebalancing may be a better solution, as it mitigates the emotional baggage associated with buying falling assets.)

Putting Cash to Work

Is it a portfolio imperative to be fully invested? Probably not. Readers of this note know that we are hardly bullish on the broad equity indexes, which likely offer positive but sub-par returns given full valuations and low earnings growth. Likewise, high quality bonds at low to negative rates are hardly a compelling reason to take on interest rate risk. In this environment, perhaps some cash is OK. But excessively high cash levels (>20%?) are an implied bearish bet with a “real” cost (factoring in inflation). With that in mind, here are a few ideas for putting some cash to work if you have too much on the sidelines. The idea isn’t to “load up the truck” on any of these but nibble a bit to reduce drag and gain some potential portfolio efficiencies.

Credit – With stocks fully valued broadly speaking and high quality bonds paying almost nothing, one of the cheaper parts of the capital market is credit; more specifically, high yield bonds and/or bank loans. While spread levels remain attractive, credit risk is elevated due both to the carnage in the energy sector (rising defaults) and recessionary fears (which we believe are overstated at this point). After adjusting for risk factors, credit isn’t “pound the table” cheap, but it is certainly worth a look.

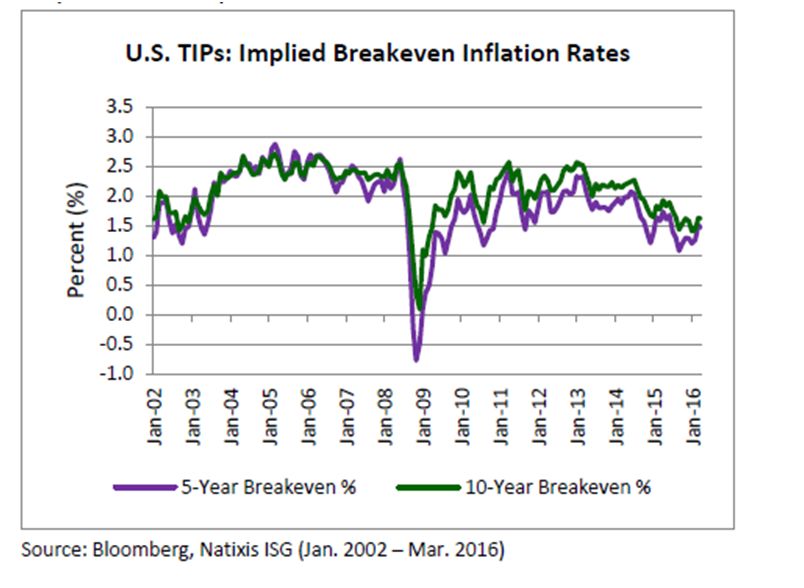

TIPS – If you hate high quality, low yielding sovereign debt, what would make Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) attractive? Granted, the inflation component of TIPS hasn’t been worth much recently, but extremely low forward expectations for inflation around the world create an asymmetric return opportunity. QE programs and a massive expansion in the global monetary base haven’t generated any significant inflationary pressures…yet. But with current breakeven rates for 5- and 10-year maturities near 1.5%, TIPs could be well rewarded from any material pickup in inflation. Conversely, with inflation expectations already so low, TIPS offer little in additional downside risk relative to nominal bonds. With ultra-low yields around the world, portfolio “ballast” (i.e., high quality fixed income) is expensive, but at least TIPS offer a possible kicker if inflation eventually surprises to the upside.

Gold – We have no idea if gold will go up or down and neither does anybody else. Gold does however have some unique asset allocation properties that investors can take advantage of. Specifically, gold is one of the few investments that can benefit from both inflationary and deflationary pressures. In the short run, gold is hardly a perfect hedge to inflation. However, in the long run, when fears of monetary expansion and “fiat currencies” grow, gold tends to rally. Conversely, gold is seen as safe haven during times of calamity or deflation and can potentially offset losses in other risk assets. Investors should keep in mind that gold is highly volatile and its correlation benefits are fleeting, so moderation is the key.

Revisit risk – Most importantly, investors can use this time to address the two most fundamental asset allocation questions: Is my asset allocation consistent with my risk tolerance and is it likely to achieve my long-term goals? There is nothing wrong with holding some cash out of the market, but make sure this is an intended bet that isn’t simply creating an unnecessary drag on returns. Long-term investment gains are a byproduct of exposing your assets to various risk premia which are ever present. Risks are like sharks’ teeth: when one falls out, another one slides into its place. If you’re waiting for the “all clear” sign from the markets, you’ll never invest (or achieve your return goals)."

David F. Lafferty, CFA

Senior Vice President – Chief Market Strategist

Natixis Global Asset Management

Weitere beliebte Meldungen: